Foot Drop: Evaluation, Localization, and Management for Spine & Peripheral Nerve Surgeons

Foot drop is a clinical sign—impaired active ankle dorsiflexion—most often due to weakness of the tibialis anterior and extensor hallucis/digitorum longus. Accurate, early localization drives imaging, prognosis, and operative timing. The common culprits are L5 radiculopathy and common peroneal neuropathy at the fibular neck; however, sciatic neuropathy, lumbosacral plexopathy, central causes, and functional disorders must be considered.

Key Takeaways

- Most common etiologies: L5 radiculopathy (disc herniation/foraminal stenosis) and common peroneal nerve entrapment at the fibular neck.

- Bedside localization hinges on patterns of weakness (inversion/eversion), sensory territories, and reflexes.

- Severe acute L5 deficits with correlating imaging merit early decompression; recovery diminishes with delay.

- In peroneal neuropathy, prompt offloading and surgical decompression for persistent or progressive deficits improves outcomes; intraneural ganglion cysts require addressing the articular branch.

- EMG/NCS is most informative after 10–21 days; serial studies refine prognosis (axon loss vs conduction block).

- Chronic foot drop (>6–12 months) may need reconstructive strategies: tendon transfer and selected nerve transfers.

Relevant Anatomy (Clinical)

- L5 myotome: ankle dorsiflexion (tibialis anterior, EHL), inversion (tibialis posterior, shared with L4), hip abduction (gluteus medius/minimus via superior gluteal nerve).

- Common peroneal nerve (CPN): branches from sciatic at popliteal fossa; wraps fibular neck; divides into deep peroneal (TA, EHL/EDL; sensation first web space) and superficial peroneal (peroneus longus/brevis eversion; sensation anterolateral leg/dorsum foot).

- Tibial nerve: plantarflexion/intrinsics; preserved strength suggests isolated peroneal lesion; involvement points toward sciatic/plexus/lumbosacral root.

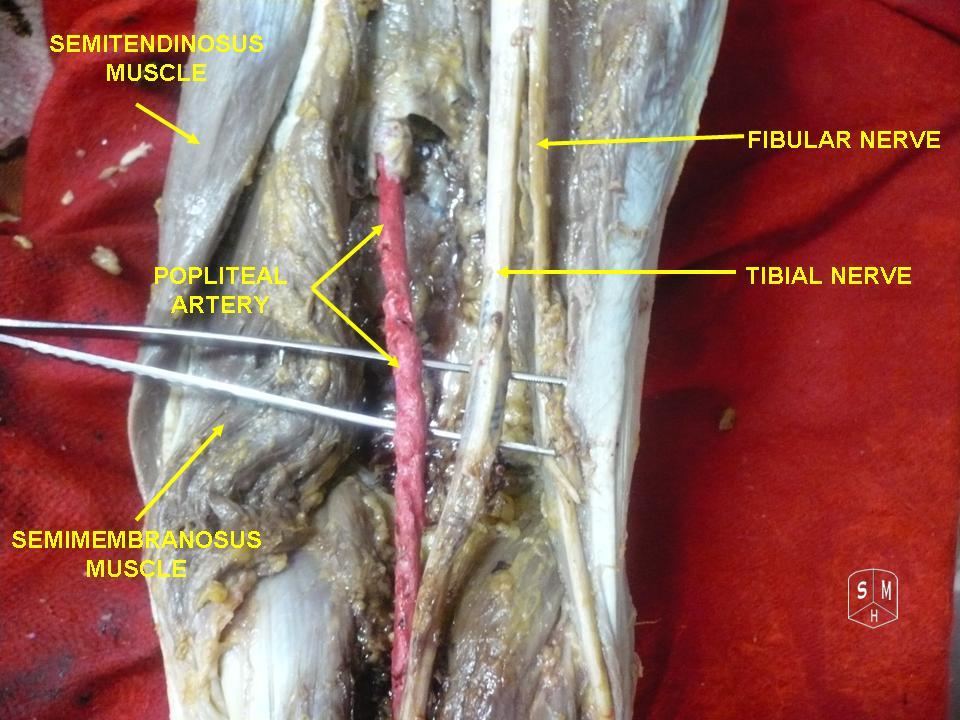

Nerves of the right lower extremity, posterior view (sciatic → tibial and common peroneal). Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain; Gray’s Anatomy plate 832).

Dissection: tibial and common peroneal (fibular) nerves at the popliteal fossa and fibular neck. Source: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0; © Anatomist90).

Differential Diagnosis and Bedside Localization

- L5 radiculopathy (root)

- Weakness: dorsiflexion (TA), toe extension (EHL/EDL), hip abduction; inversion often weak (tibialis posterior via tibial nerve, L4–5).

- Sensory: dorsum of foot, medial plantar aspect possible; variable. Positive straight leg raise if disc herniation.

- Reflexes: typically preserved ankle jerk (S1); medial hamstring may be reduced.

- Pain: back and radicular leg pain common; foraminal stenosis can cause predominantly leg pain.

- Common peroneal neuropathy at fibular neck (mononeuropathy)

- Weakness: dorsiflexion + toe extension; eversion weak (superficial peroneal). Inversion preserved (tibialis posterior intact) — a key discriminator from pure L5 root.

- Sensory: anterolateral leg and dorsum of foot; first web space (deep peroneal). Sparing of plantar foot.

- Provocative: Tinel at fibular neck; reproduced paresthesias with compression/leg crossing; weight loss, tight casts/braces, habitual squatting, prolonged lithotomy, TKA, fibular head trauma.

- Sciatic neuropathy (peroneal division vulnerable)

- Weakness: peroneal > tibial division typically; may include hamstrings. Plantarflexion often partially reduced if tibial involved.

- Sensory: peroneal + tibial distributions; posterior thigh sensation may be affected.

- Etiologies: hip trauma/dislocation, piriformis/deep gluteal syndrome, iatrogenic (hip arthroplasty), injections, tumors.

- Lumbosacral plexopathy

- Patchy deficits crossing multiple root territories; pain variable. Consider radiation, retroperitoneal hematoma, diabetes (diabetic amyotrophy variant), malignancy.

- Central causes

- Stroke (rare isolated foot drop; usually upper motor neuron signs), parasagittal meningioma, spinal cord lesions (check UMN signs, level).

- Others

- Motor neuron disease, CIDP/GBS variants, functional neurologic disorder.

Practical discriminators

- Inversion weakness → favors L5 radiculopathy/sciatic vs preserved inversion → favors CPN.

- Hip abduction weakness (Trendelenburg) → supports L5 root.

- Isolated first webspace numbness → deep peroneal involvement.

- Back pain/radicular maneuvers positive → root; fibular neck Tinel → CPN.

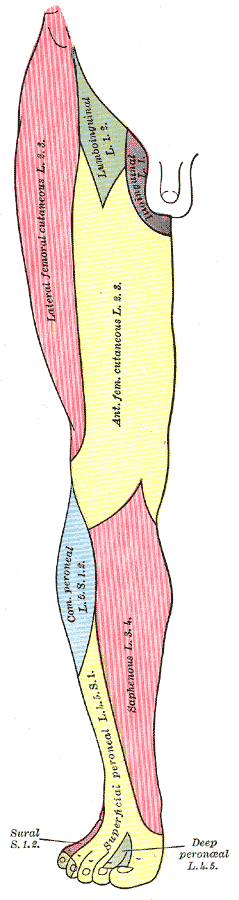

Segmental distribution (cutaneous nerves/dermatomes), anterior view. Useful when correlating L5 sensory findings. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain; Gray’s Anatomy plate 826).

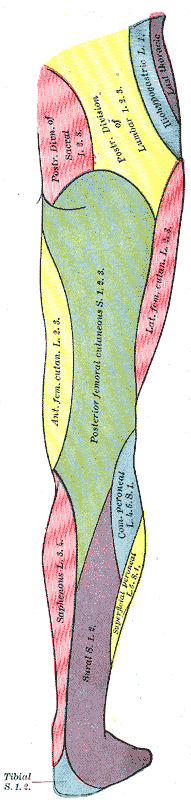

Segmental distribution (cutaneous nerves/dermatomes), posterior view. Highlights posterior L5/S1 territories. Source: Wikimedia Commons (Public Domain; Gray’s Anatomy plate 831).

History and Examination Checklist

- Onset/time course: acute (disc herniation, compression palsy), subacute (intraneural ganglion, mass), chronic (stenosis, neuropathy).

- Pain profile: back and leg (root); lateral knee/fibular neck pain/paresthesias (CPN); buttock/hip pain (sciatic).

- Precipitating factors: weight loss, leg crossing, bedrest, casts, brace, arthroplasty, squatting, prolonged lithotomy, trauma.

- Weakness pattern: dorsiflexion, toe extension; eversion vs inversion; plantarflexion; hip abduction.

- Sensory: first web space, dorsum foot, lateral leg, plantar foot sparing.

- Reflexes: ankle jerk (S1), patellar (L3–4), medial hamstring.

- Gait: steppage, foot slap; compensatory hip/knee flexion.

- Red flags: cauda equina (saddle anesthesia, urinary retention), progressive profound deficit, severe intractable pain.

Grading dorsiflexion (MRC)

- M0–M5; track serially. Profound M0–M2 with correlating pathology often warrants early intervention.

Imaging Strategy

- Lumbar MRI: if L5 radiculopathy suspected (disc herniation, foraminal stenosis, synovial cyst). Include foraminal views; consider contrast if tumor/infection.

- Knee/proximal fibula MRI or high-resolution ultrasound: suspected CPN entrapment, intraneural ganglion cyst, mass; ultrasound can localize and guide aspiration but addressing the articular branch of the superior tibiofibular joint is pivotal to prevent recurrence.

- Hip/pelvis MRI: suspected sciatic neuropathy/plexopathy; evaluate post-arthroplasty patients.

- Whole-body considerations: in neoplasm or radiation plexopathy.

Electrodiagnostics (EMG/NCS)

- Timing: earliest denervation changes at 10–14 days; best yield at 3–4 weeks. Repeat at 8–12 weeks for trajectory.

- NCS: peroneal CMAP amplitude (EDB/TA) correlates with axon loss; conduction block/demyelination suggests better prognosis.

- EMG sampling: TA, EHL, peroneus longus, tibialis posterior, gluteus medius, paraspinals. Paraspinal denervation implicates root.

- Prognosis: preserved CMAP and early recruitment → favorable; absent CMAP with fibrillations → guarded, consider earlier reconstructive planning if no reinnervation by 4–6 months.

Management Algorithms

Initial measures for all

- Protect limb: ankle-foot orthosis (AFO) to prevent trips and equinus contracture; night splinting as needed.

- Physical therapy: ROM, strengthening of preserved muscles (evertors/invertors), proprioception, gait training; consider functional electrical stimulation (FES) for dorsiflexion.

- Address reversible factors: remove external compression, adjust casts/braces, cease leg crossing, optimize glycemic control and nutrition.

Ankle–Foot Orthosis (AFO) for foot drop. Helps prevent trips and contracture while recovery occurs. Source: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0; © Pagemaker787).

L5 Radiculopathy

- Indications for early decompression: severe/progressive motor deficit (≤ M3), concordant L5 compression on MRI, refractory pain; earlier (under 2–4 weeks) generally yields superior dorsiflexion recovery versus delayed.

- Procedures: microdiscectomy for herniation; for foraminal/far lateral stenosis consider foraminotomy with targeted decompression; be mindful of exiting L5 root and dorsal root ganglion sensitivity.

- Prognosis: duration of deficit, age, preoperative grade, and presence of EMG denervation influence recovery. Early M4+ recovery common when decompressed promptly.

Common Peroneal Neuropathy (Fibular Neck)

- Immediate: remove compression, padding, avoid leg crossing; AFO.

- Operative indications: space-occupying lesion (e.g., intraneural ganglion), progressive deficits, no clinical/EMG improvement by ~6–12 weeks in compressive entrapment, laceration/traction injuries requiring exploration.

- Techniques: neurolysis/decompression at fibular tunnel; for intraneural ganglion, disconnect articular branch to the superior tibiofibular joint and evacuate cyst to minimize recurrence.

- Prognosis: demyelinating lesions recover well post-decompression; severe axon loss may incompletely recover and need late reconstruction.

Sciatic Neuropathy/Plexopathy

- Treat underlying cause (hematoma evacuation, tumor resection, hardware revision, release of deep gluteal entrapment).

- Consider exploration for iatrogenic injury with severe deficit and concordant imaging/electrodiagnostics.

Reconstructive Options for Chronic Foot Drop

Timing principles

- Motor endplates decline after 12–18 months; aim to reinnervate target muscles by ~6–9 months when possible.

Nerve-based strategies (selected cases)

- Distal nerve transfers: fascicles from tibial nerve (to soleus) to deep peroneal branches (to TA/EHL) in proximal lesions with viable distal targets; best within 6–9 months.

- Grafting/repair: acute lacerations; long gaps have poorer outcomes.

Tendon transfers (reliable for long-standing deficits)

- Posterior tibialis tendon (PTT) transfer: through interosseous membrane to dorsum of foot; powerful and time-tested; requires intact PTT and supple ankle/hindfoot; balance with peroneus longus/brevis procedures as needed.

- Alternatives/adjuncts: peroneus longus to brevis balancing, Achilles lengthening if equinus contracture.

Decision framework

- If no EMG reinnervation by ~4–6 months and severe axon loss → discuss nerve transfer vs early planning for PTT transfer if root cause not surgically reversible or recovery unlikely.

- Long-standing (>9–12 months) M0–M2 with absent CMAP → tendon transfer preferred.

Postoperative rehab

- Protected immobilization per procedure; progressive strengthening and gait retraining; orthotic weaning as function returns.

Special Situations and Pearls

- Intraneural ganglion of CPN: address articular branch to superior tibiofibular joint to reduce recurrence; consider joint pathology.

- Post-arthroplasty palsy: assess limb lengthening, hematoma; urgent imaging if severe pain/swelling.

- Rapid weight loss/ICU neuropathy: compression at fibular head from bedrest; frequent repositioning and padding.

- Diabetic patients: mixed etiologies; optimize glucose; higher risk of incomplete recovery.

- Pediatrics: consider tethered cord, peroneal nerve injury with proximal tibial/fibular fractures; growth-friendly orthoses.

- Red flags: bowel/bladder changes, saddle anesthesia, bilateral deficits → urgent spinal imaging for cauda equina.

Suggested Workup Pathways

Suspected L5 radiculopathy

- MRI lumbar spine with foraminal attention → correlate with exam → severe/progressive deficit → early decompression; otherwise conservative care with close follow-up and EMG at 3–4 weeks.

Suspected CPN entrapment

- Ultrasound/MRI knee and fibular tunnel; relieve external compression; if progressive or structural lesion → decompression (and articular branch management if intraneural ganglion).

Unclear localization

- EMG/NCS at 3–4 weeks sampling paraspinals and limb muscles; targeted imaging based on findings.

Prognosis

- Best outcomes with early, localization-driven treatment.

- Demyelinating mononeuropathies recover well after decompression.

- Axon loss (low CMAP, dense fibrillations) portends slower, incomplete recovery; consider reconstructive planning if no reinnervation trajectory by 4–6 months.

- Chronic denervation beyond 12 months reduces nerve-based reconstruction success; tendon transfer yields dependable gait improvement.

References and Further Reading (selected)

- Kim DH, Kline DG. Management and results of peroneal nerve lesions. Neurosurgery.

- Spinner RJ, et al. Intraneural ganglion cysts of the peroneal nerve: pathogenesis and treatment algorithm.

- Postacchini F, Cinotti G. Timing of surgery for motor deficit due to lumbar disc herniation.

- Wilbourn AJ. Electrodiagnosis of peroneal neuropathy and L5 radiculopathy: differentiating features.

- Mackinnon SE. Nerve transfers in lower extremity reconstruction.

You can contact us at @bdthombre(https://www.linkedin.com/in/bdthombre/ ) on LinkedIn.